Despite the government’s attempts to silence dissent, Buenos Aires welcomed the WTO with action and protests, write Paula Serafini and Martín Vainstein

From 10-13 December, Argentina hosted the World Trade Organization ministerial conference. This biannual meeting, in which countries and customs unions discuss the rules governing international trade, arrived at a time of political flux. It touched a nerve in Argentina, where indigenous struggle against multinational corporations and the government’s extractivist policies is boiling over.

The context

Since the presidential inauguration of Mauricio Macri in December 2015, the right-wing coalition government has been working tirelessly to ‘open Argentina to the world’.

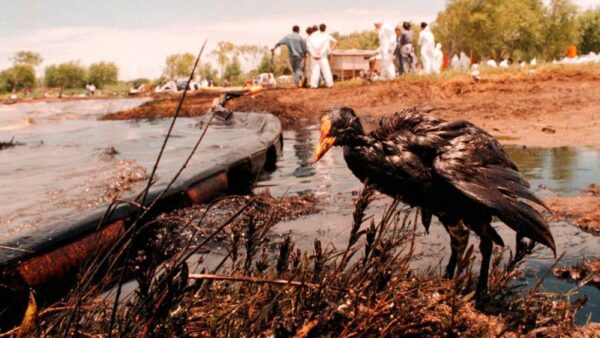

In practice, this has meant fiscal benefits for the mining and fossil fuel sector. Macri’s government has intensified the neoliberal agenda that was instituted in the 1990s during Carlos Saúl Menem’s government, with legal reform, privatization, and the encouraging of Monsanto’s agricultural model, and furthered during the administration of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner.

While previous administrations neglected indigenous rights – and there were several cases of indigenous activists being murdered – what characterizes the current government is the escalating violence with which it is imposing its agenda.

The country is still reeling from the disappearance of Santiago Maldonado in August 2017, a white ally supporting the Mapuche community in Patagonia. Santiago was taking part in a demonstration defending ancestral land from the clothing empire Benetton Group, a conflict that extends back to 2007. Four months and five nationwide popular mobilizations later, his body appeared drowned in a nearby river, bringing back memories of Argentina’s military dictatorship, where dissidents regularly ‘disappeared’ at the hands of right-wing death squads.

Just two weeks ago, Patagonia was once again witness to violent repression. Rafael Nahuel, a 22-year old Mapuche was shot dead in the back by security forces during a raid in recuperated ancestral land inside a national park.

Santiago and Rafael’s deaths took place as capital sought to expand into new territories in the country’s south, as it seeks to exploit profit from unspoiled lands. The violence against dissidents is matched by a racist programme of stigmatization of the Mapuche people carried out by mainstream media outlets, which not only delegitimize the Mapuche people’s claims, but also portray them as violent and a threat to national security.

An alternative to the WTO

But despite the government’s attempts to silence dissent, Buenos Aires welcomed the WTO meeting with a week of action in the form of protests, festivals and the ‘People’s Summit’, a forum for discussion and the building of alternatives to the current economic model.

Among the events that made up the summit was the Forum and Assembly for the Commons, Climate Justice and Energy Sovereignty. The event featured intellectuals, frontline community representatives, activists and trade unionists from Argentina and Latin America who came together to share experiences and discuss alternatives to extractivism. These, we consider, are some of the key points to take away from the forum, looking ahead towards a new year of struggle, with a G20 meeting taking place in Buenos Aires a year from now.

-

We need to talk about capitalism. A number of speakers stressed the need to move away from discussions on extractivism as an environmental problem or an issue that is constrained to the extractive industries exclusively. Extractivism is a manifestation of the capitalist system more generally, and we need to get to the root of the problem in order to fully confront it.

-

Sovereignty. ‘Energy for what, and for whom?’ was a focal point. A representative of the Assembly Jáchal No Se Toca (Hands off Jáchal), which is resisting open-pit mining, later mirrored this asking: ‘mining for what, and for whom?’ While challenging prevailing patterns of production and consumption, these questions also highlighted the issue of sovereignty over the commons.

-

Intersectionality and decoloniality. Several speakers, including Karin Nansen from REDES Amigos de la Tierra Uruguay (Friends of the Earth Uruguay), addressed the links between extractivism and women’s oppression. Calls were made to strengthen the connections between movements against extractivism and workers’ rights. In his opening remarks, Felipe Gutiérrez from the grassroots movement Marabunta invited us to challenge the idea of our Latin American ‘nations’ as homogeneous constructions dictated by European thinking, and to recognize the plurality of nations that make up our territories.

-

Supporting the frontlines. Speakers from a number of provinces in Argentina made reference to the centralization of decision-making in the country which, topped with the feudal nature of many provinces, restricts democratic rights. They called for allies in the capital to represent and support frontline communities.

-

New ideas. With regards to steps forward, Marta Maffei, a union leader and former congresswoman behind Argentina’s laws for the protection of glaciersand the conservation of forests, concluded her speech calling for the production of new forms of knowledge that are independent from the corporate lobbying corrupting universities across the country, and for the development of a robust programme of environmental education. In her words: ‘There is no capitalism without cultural domination; what we need is a radical cultural change.’

Paula Serafini is an artist, educator and researcher working on creative resistance to extractivism. She is a Research Associate at University of Leicester.