Community tell of devastating environmental impact on land where their animals grazed

Uki Goñi.– The roar of the burning gas well could be heard almost a mile and a half away, from atop the high plateau where Albino Campo Maripe stood, looking down at the orange flames lapping the earth in the distance.

When he was a child, the 60-year-old Mapuche chief used to ride there bareback. Those days are gone for ever. The once-pristine landscape is now dotted with fracking wells and the white patches of land cleared for even more.

The panoramic view is nonetheless overpowering. Two crystal-blue lakes, whose far shores blend with the horizon, cling to the edge of an arid and wind-buffeted Martian landscape of red sandstone, rugged promontories and wide beaches.

The ancient and spectacular rock formations of Neuquén province in Argentina’s Patagonia region are a paleontologist’s dream, rich with dinosaur fossils. But the image quickly fades to the sight and sound of the fracking well that exploded on 14 September and burned continuously for 24 days, spewing hot gas and other elements into the air from nearly two miles below ground.

The raging fire was finally put out on Monday by a team of experts who flew from Houston with 56 tons of special equipment. “This shouldn’t be happening,” Campo Maripe said, “but these are the consequences of fracking.”

Fracking accidents happen regularly in Vaca Muerta (Dead Cow in Spanish), one of the world’s largest shale oil and gas reservoirs. In 2018 alone, there were an estimated 934 incidents at 95 wells.

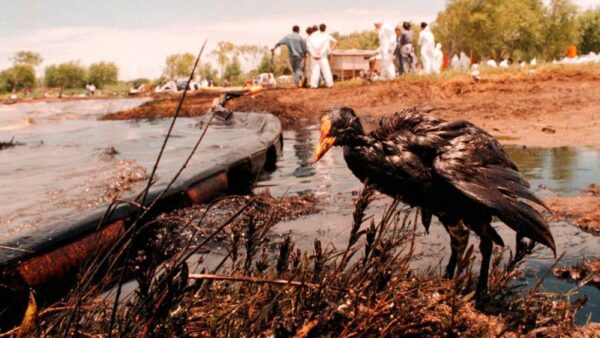

There have been leaks from drilling sites, and claims from local people of water pollution and increased ill health affecting them and their livestock.

For Argentina’s leaders there is a bigger picture. They believe the shale reservoir can rescue the country from its ongoing economic crises.

“This province will transform us into a world power,” the president, Mauricio Macri, said on Tuesday to a crowd of 3,000 people in Neuquén, referring to the nearly 2,000 fracking wells that have been drilled there since the discovery of the deposits was announced in 2011.

Twenty companies own a total of 36 concessions in Vaca Muerta, covering a combined area of about 8,500 sq km (3,300 sq miles).

The Argentine oil company YPF leads the pack with 23 areas, of which 16 are operational, in partnership with the US firm Chevron.

Fracking accidents happen regularly in Vaca Muerta (Dead Cow in Spanish), one of the world’s largest shale oil and gas reservoirs. In 2018 alone, there were an estimated 934 incidents at 95 wells.

There have been leaks from drilling sites, and claims from local people of water pollution and increased ill health affecting them and their livestock.

For Argentina’s leaders there is a bigger picture. They believe the shale reservoir can rescue the country from its ongoing economic crises.

“This province will transform us into a world power,” the president, Mauricio Macri, said on Tuesday to a crowd of 3,000 people in Neuquén, referring to the nearly 2,000 fracking wells that have been drilled there since the discovery of the deposits was announced in 2011.

Twenty companies own a total of 36 concessions in Vaca Muerta, covering a combined area of about 8,500 sq km (3,300 sq miles).

The Argentine oil company YPF leads the pack with 23 areas, of which 16 are operational, in partnership with the US firm Chevron.

For the environmentalist Maristella Svampa, the promise that Vaca Muerta could turn Argentina into a new Saudi Arabia is a myth, like that of El Dorado, the city of gold the Spanish conquistadors searched for in South America. “It’s the magical illusion of sudden wealth,” she said.

Neuquén’s indigenous Mapuche people claim Vaca Muerta has brought them not wealth, but discrimination, dispossession and health problems.

The Campo Maripe community, comprising about 125 people among 35 families, is one of more than 40 Mapuche communities in Neuquén.

“When we went to school the other students would yell: ‘Here come the Indians,’” says Mabel Campo Maripe, 52, who shares community chief duties with her brother Albino. “Those same people today refuse to accept we are Mapuches because that would give us a right to our land.”

They say the denial of their cultural identity is being used by the Neuquén authorities to refuse the Campo Maripe community legal rights over the Loma Campana plateau, where they say they have grazed their cattle and goats for nearly a century. Pockmarked with close to 500 fracking wells that have sprung up in the past seven years, the plateau is the centre of the fracking boom.

Summer temperatures reach 40C (104F); in winter they dip to -14C. There are no trees, only sparse shrubs that provide subsistence pasture for the cattle and goats of the Campo Maripe community.

“The oil companies entered our land without our permission,” claims the elder Campo Maripe. The fracking wells took a quick toll on their animals, he says. “We had goats born without jaws, without mouths.”

In 2014, the community began blocking the access road used by oil company trucks to reach the Loma Campana plateau. “First we blocked the road for two weeks, then for 48 days and then again for another 48 days,” says Campo Maripe.

They occupied fracking towers and even the YPF offices in the capital city of Neuquén. Finally, an agreement was reached for a special committee, consisting of government and Mapuche-appointed experts, to determine the community’s claim on about 17,000 hectares (42,000 acres) in and around Loma Campana.

“We were able to determine that the Campo Maripe clan has occupied the land continually since at least 1927, when they started paying pasture rights to the national government,” said Jorgelina Villarreal, an anthropologist who formed part of the committee. “We found government records, even an army map, that show they were the first recorded settlers of Loma Campana.”

But in 2015, the authorities refused to accept the committee’s findings. The then governor Jorge Sapag said the report failed to prove the community had inhabited the area in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries and therefore their claim to the plateau was invalid. He said: “The plateau belongs to the province.”

Villareal said: “His reasoning is ridiculous. Argentina didn’t even exist in the 17th and 18th centuries, but the Mapuches were already here.” The authorities offered the clan the title deed to a mere 700 hectares. The offer was refused.

Oil companies say they are trying to work with the indigenous communities but YPF pointed to the 2015 ruling and reiterated: “Campo Maripe has never inhabited the extensive land they are claiming for.”

A spokesman said: “Their houses and cultural or productive activities are several kilometres away from YPF and Chevron’s operations. Nevertheless, the community still claims they should have rights on the lands where YPF and Chevron operate.”

The oil companies say their work does not contaminate water sources because it occurs 3,000 metres (9,850ft) below ground, while the water tables are at a depth of only 200 metres.

But Campo Maripe claims the problem is not seepage from below, but from above. “They drilled about 400 wells contaminating everything. They dug pits next to the wells where they dumped the waste without any treatment and threw limestone on it to cover it up. We lost our best land.”

Albino, Mabel and other family members say they have suffered a multitude of health problems since the fracking began.

“One of our sisters and her husband died of cancer in 2017,” says Mabel. “The fracking has affected our bones, which become decalcified. I had to have a titanium spine implant; another sister also needs one. Albino had an operation on his arm because of bone loss.”

Both siblings claim doctors have privately told them the cause is contamination from the wells. “They are scared to talk,” says Mabel. She says one worried doctor asked her: “Are you recording me?”

“Last year, the grandson of another sister was born with his intestines outside his body. They had to operate [on] him to put them in,” says Mabel.

Then there are the permanent headaches, and the smell. On hot, windy days the fields smell like a petrol station.

The Guardian asked YPF about the fears of contamination and possible health impacts, including claims of cancer, respiratory ailments and skin lesions. It denied there was a problem.

“At YPF we are committed to operate with the highest standards. Operational excellence is key and we work permanently to improve and implement solutions that minimise the potential impacts that our activity could generate,” it said. “In the special case of Loma Campana, the area we develop in partnership with Chevron, no incidents of any kind have been recorded since the beginning of operations in 2013.”

The arrival of waste disposal contractors has brought a separate set of problems. A Greenpeace team took samples from the open-air waste pits on Loma Campana and released the results to the Mapuche Confederation of Neuquén, which last October opened a lawsuit against the Treater waste disposal plant, alleging that Treater had handled waste for many of the fossil fuel companies mining in the area.

“We are concerned about leakage from the waste pits into the ground as well as by the wind carrying volatile particles into the air from the mountains of waste above the pools,” says Natalia Machain, executive director of Greenpeace Argentina, which joined the lawsuit as plaintiff this year.

Treater has denied any contamination. “We are not a waste dump. We are an environmental services company that treats waste from the oil industry.”

But the Neuquén legislator Santiago Nogueira is pressing for waste management laws because, he says, “the province does not have enough capacity to process the amount of waste generated by Vaca Muerta”.

Treater is only one of many open-air waste pits dotted across Vaca Muerta. A large mound rises above the Comarsa waste plant about 4 miles (6km) outside Neuquén. Closed by the authorities because of its proximity to a large urban area, the plant no longer receives waste, but bulldozers are constantly at work turning over the mounds of earth on its grounds.

Sections of the cement containment wall around the plant have collapsed.

“There are over 300,000 cubic metres of waste still piled at Comarsa,” said Nogueira. “The whole waste treatment system is insufficient.”

Vaca Muerta has yet to prove its economic viability. Experts say the government’s expectations are hampered by the high cost of fracking in Argentina and the lack of adequate gas transport and waste disposal infrastructure, aggravated by a shaky economy.

The country has spent billions of dollars in direct handouts to lure

investors. “Oil companies aren’t extracting hydrocarbons from Vaca Muerta. They’re extracting subsidies,” says Enrique Viale, an environmental lawyer and anti-fracking campaigner.

The subsidies are ultimately unaffordable for Argentina, according to a report released in March by the Cleveland-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

In January the International Monetary Fund, which had put together a $57bn bailout for Argentina in 2018, demanded a trimming of the subsidies. The industry responded with layoffs, the threat of lawsuits against the government and production cuts. “The abrupt reduction in Argentina’s production subsidy programme … is shaking investor confidence,” the report states.

However grim the outlook for the oil and gas companies, it is the Mapuche indigenous people who are bearing the highest cost for Argentina’s dream of a fracking bonanza.

“As Mapuches, we’re not fighting for just ourselves or our community,” says Albino Campo Maripe. “We want our children and grandchildren to know that we fought for something that belongs to everyone. Water is life. Every plant is life. The greed of governments is killing the world. The world is not going to end. We are going to end, because we’re killing ourselves.”