Argentina recently announced plans to start producing green hydrogen at scale in Patagonia. Will it succeed?

By Julián Reingold / Energy Monitor.- Argentina has pledged a green recovery back from unsustainable debt and Covid-19. However, there are contradictions. On the one hand, it supports the production of “green” hydrogen from solar and wind power; on the other, it continues to invest in oil, gas and silver extraction, a highly water-demanding activity. This jeopardises its international commitments to reduce emissions to tackle climate change, which is already affecting the country’s economy due to water stress in many of its provinces.

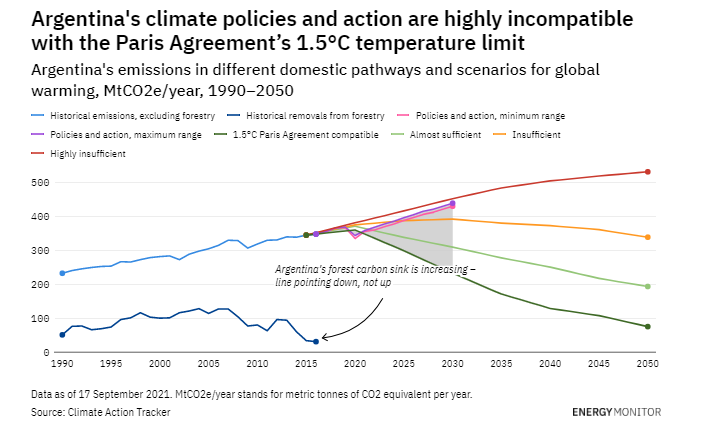

Ahead of COP26, Argentina updated its climate goal to limit annual “net” greenhouse gas emissions to 349 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2e) by 2030, an increase of 35% above 1990 levels (emissions in 2018 were 366MtCO2e). However, this goal is not compatible with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C, according to a report on Argentina by the Climate Transparency partnership. For that, emissions in 2030 would need to be around 210MtCO2e, or 9% below 1990 levels.

Argentina aims to be carbon neutral by 2050. In order to achieve that, non-profit Climate Action Tracker says the country must support low-carbon Covid-19 recovery measures, including phasing out the exploration and extraction of fossil fuels via projects such as the Vaca Muerta gas field (the world’s second-largest shale gas deposit), eliminating fossil fuel subsidies and addressing the country’s increasing dependency on meat production and exports.

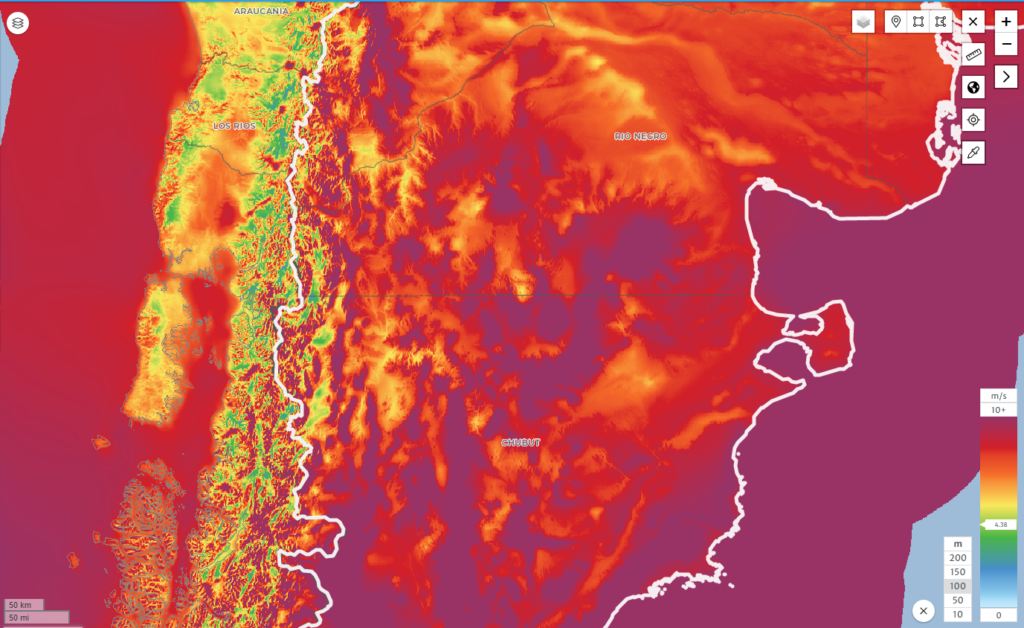

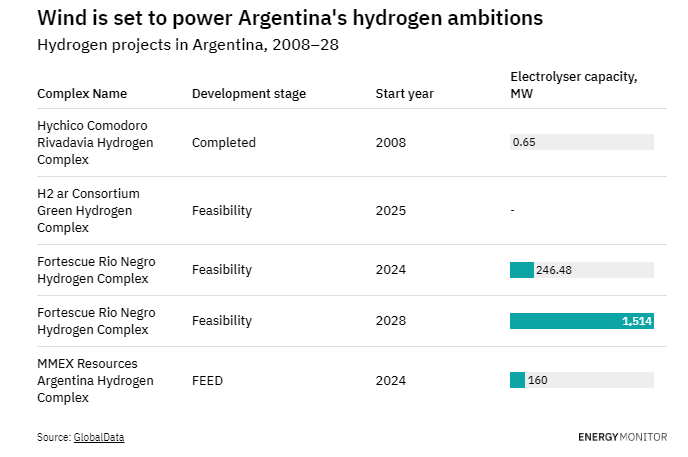

Argentina itself is keen to develop a green hydrogen export hub for developed nations. The Argentinian government and Australian company Fortescue Future Industries (FFI) announced a major investment plan of $8.4bn (1.2trn pesos) by 2028 to produce green hydrogen in Argentina at CO26 last November. The so-called Pampas project will take place in the coastal town of Sierra Grande in Río Negro, at the northern end of Patagonia. The plan is to leverage the extraordinary Patagonian winds. It would be one of the largest investments in the history of Argentina, bringing much-needed foreign currency and money into the country’s coffers.

Marcelo Kloster, a government advisor on national economic development and a board member at energy technology company IMPSA, estimates that Argentina could produce as much as 7.5 million tonnes of green hydrogen per year. According to the Ministry of Production, this could amount to $15bn in hydrogen exports by 2050, which is what soybean exports – of which Argentina is one of the world’s top producers – contributed to the country in 2020.

However, it will require massive deployment of renewable energy, something Argentina has struggled with in recent years. Despite a 2015 Law of Renewable Energies and the 2016 RenovAr plan – a strategy that aimed to incorporate 10,000MW of renewable energy into its power mix and reach 20% renewables by 2025 – Buenos Aires is falling short of its objectives. By March 2019, the installed renewables capacity was just 1,775MW, about 6% of the power mix: 904MW came from wind, 505MW from hydro, 207MW from solar and 159MW from biomass. In 2021, only 13% of total electricity demand was supplied from renewable sources. Argentina has the eighth-highest share of fossil fuels in electricity production in the G20.

Oil, gas and silver

The Chubut province exemplifies Argentina’s history of resource extraction. Its city of Comodoro Rivadavia was the starting point for the operations of Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), the state-owned Argentine energy company, in 1922. The heart of the fossil fuel industry is now in Vaca Muerta, where growth in natural gas production will be accompanied by a new pipeline to the west of the Buenos Aires province, to decrease gas imports and eventually have a leftover stock for export.

“[Argentina’s net zero plan] appears completely divorced from its public policies, which promote the expansion of the hydrocarbon frontier through fracking,” the renowned Argentine researcher and sociologist Maristella Svampa told Energy Monitor in an interview. “[The government foresees] expansion of the Vaca Muerta wells, construction of gas pipelines, and, from 2022, oil exploration in deep waters.”

“The ‘gas export mandate’ appears to be key [to the current government] to combat Argentina’s external deficit and over-indebtedness,” Svampa says.

Although Chubut is the fourth province in terms of exports abroad, its finances are not thriving, causing social unrest as public employees spend months without pay in the midst of high levels of unemployment. Recently, its provincial authorities aimed to kickstart the extraction of silver through an open pit mine called project ‘Navidad’, even though the project has faced strong opposition from grassroots movements across Chubut since 2003. As Svampa points out, the answer to that problem was “more extractivism, less democracy and more repression”.

However, Comodoro Rivadavia’s mayor, Juan Pablo Luque – whose political force, Frente de Todos, originally supported the mining project – recently said that silver extraction is “currently off the table”.

Chubut began developing its wind potential in the late 1990s and still has the largest wind farms in the country. However, the local government’s obsession with developing the province through open pit mining and the political instability that engendered diverted investors towards Río Negro. It opened an opportunity for Rio Negro to get the the FFI project and develop a series of wind farms from scratch – along with the creation of a new port in Sierra Grande – to export green hydrogen.

Kloster says the main reason Río Negro was selected for the FFI project was the availability of thousands of hectares of public land for the installation of wind farms, the hydrogen plant and the port. Chubut has great wind power potential too, he added, but much of the land is under private ownership.

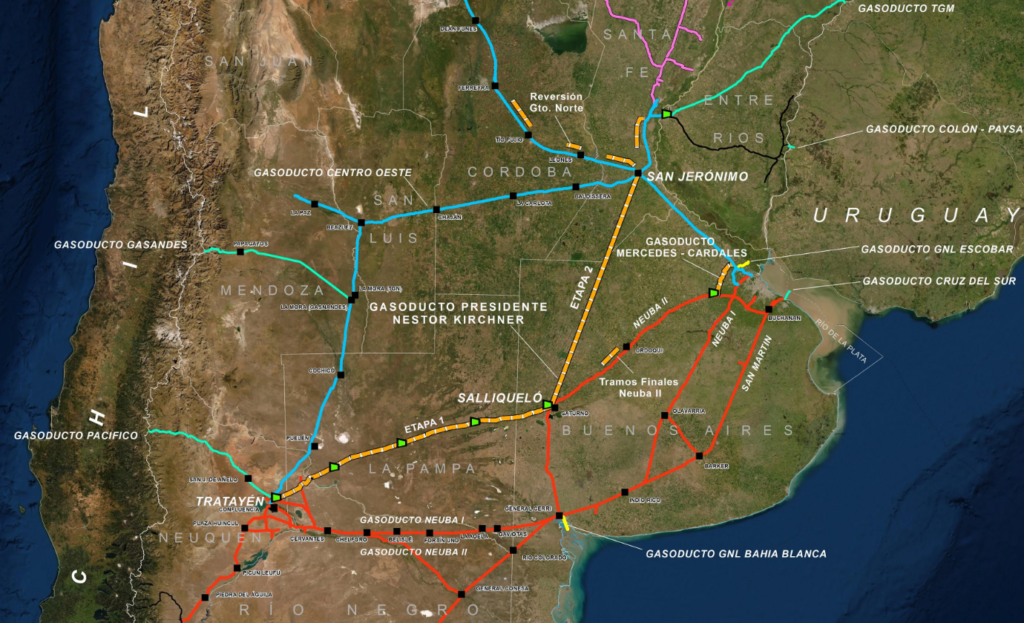

For all its potential benefits, the FFI project will have little impact on Argentina’s decarbonisation plans, since the green hydrogen produced will not feed into its domestic energy consumption. Instead, the Argentine government is racing to complete the natural gas pipeline from the Vaca Muerta shale gas reservoir to the Province of Buenos Aires to reduce domestic gas prices and eventually have gas for export. The goal is to finish by the winter of 2023 – just before the next presidential elections.

This pipeline will largely be financed by Argentina’s Covid-19 recovery fund. The first stage of the pipeline will cost some $1.5bn. Once the pipeline is operational, Argentina should save between $1.3bn and $1.5bn in gas imports. New fossil gas capacity would cover a deficit of ten billion cubic metres of gas per year (bcm/y) between what Argentina produces – 45bcm/y – and its total demand of 55bcm/y.

From wind to green hydrogen in Argentina

One would expect an industrial oil city like Comodoro Rivadavia to look luxurious and wealthy, but the dusty roads, lack of water access for its people and old buses make it look more like Detroit than Dubai. It is one of the best wind sites in the world, but a province like Chubut has yet to become a leader of Argentina’s energy transition.

“[We] have the capacity, but just lack the political determination and national support to exploit the province’s potential for green hydrogen,” Comodoro Rivadavia’s Mayor Luque told Energy Monitor.

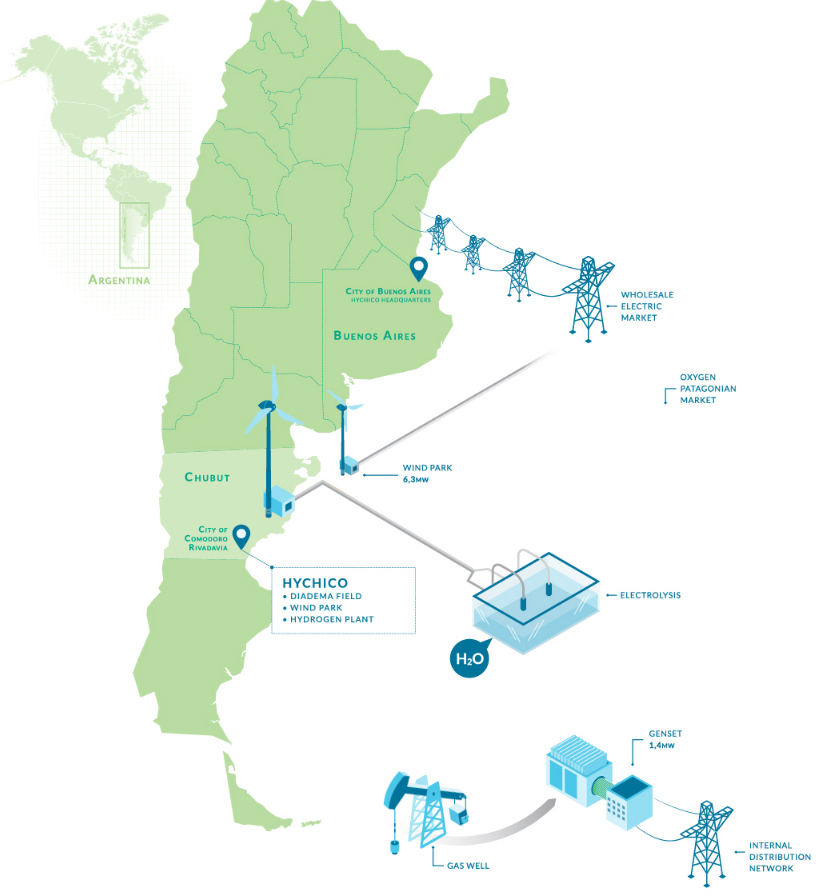

Of the 961 wind turbines in Argentina, Chubut has 365 (38% of the total). Since 2009, the Capsa-Capex group, through the company Hychico, has been producing around 92 tonnes (t) of renewable hydrogen per year near Comodoro Rivadavia. Its hydrogen is mixed with natural gas (up to 42%) to fuel a 1.4MW generator, which fuels an oil and gas field.

Flavio Tuvo, a representative of Hychico, says a commercial-scale project would imply exporting most of the hydrogen produced. The objective of the existing project was to gain experience and have the know-how to be prepared for a large-scale project. Tuvo considers that Chubut has a very high potential in wind energy, with probably even better conditions than Río Negro.

In southern Patagonia (Chubut and Santa Cruz), average wind speeds range between 9.0 and 11.2 metres per second (m/s), whereas in the north (Neuquén and Río Negro) wind speeds range from 7.2 to 7.8m/s.

Both Tuvo and Kloster agree Argentina needs a new hydrogen law to have a stable legal framework and ease new investments – of at least $800m per project – by allowing multinationals to operate freely. An earlier hydrogen law from 2006 expired in September 2021 and there are already three new legislative drafts ready to be analysed by Parliament.

“The current energy crisis made European countries revise their strategies: now Argentina has the opportunity… to be a key facilitator in the energy supply chains, particularly in the Western Hemisphere,” Kloster says.

Do Argentine communities want green hydrogen?

On the road through the empty plateau that separates Comodoro Rivadavia from Trelew – in northern Chubut – you can only hear one sound: the blasting of the wind. Yet the unknown environmental impacts of high-scale hydrogen production through wind farms are a concern for communities in Patagonia, which have already rejected other extractive initiatives.

“They keep insisting on bringing ‘development’ through silver extraction instead of discussing new ideas,” environmental activist Pablo Lada told Energy Monitor in Trelew, one of the epicentres of the ‘Chubutazo‘ riots against the province’s open pit silver mine project. “Personally, I would prefer the impact of 2,000 windmills to open pit mining.”

Svampa worries mining will exacerbate water shortages in the region. In contrast, Tuvo says, green hydrogen production requires very little water, with an estimated 7–8t of water required for each tonne of green hydrogen – and that could be seawater after desalination. Tuvo does note that the roads, ports and land for wind farms – at least 35–40ha – must take into consideration potential claims from local communities, both in Río Negro and Chubut.

However, NGOs insist the chemical properties of hydrogen require close attention. According to the report ‘Hydrogen: the new panacea?‘, by Spanish NGOs Ecologistas en Acción and the Catalan Observatori del Deute en la Globalització, the very small size of the molecule leads to a high risk of leakage. Moreover, hydrogen is highly flammable, although this risk is mitigated by its high diffusiveness. It also requires very high pressure to store, which can damage the materials used for storage and transport (corroding pipes, for example), and burns with a colourless, odourless flame, which makes detection of fires and leaks difficult.

The renewable power needed to produce the hydrogen can also be harmful. In the province of Neuquén, farm animals unaccustomed to large bulldozers and incessant noise began to get sick when wind farms were built nearby.

Kloster says only 8% of the designated land for the project would be occupied by wind turbines and that very few people live on the plateaus of Río Negro due to strong winds and freezing winters, which can reach -35°C. The plan to use desalinated seawater would not result in damaging salt residues either, he added, and part of the extracted salt could be used to supply other industries. The risks of hydrogen leaks and explosions would also be reduced to a minimum, as the hydrogen would be stored as liquid ammonia.

Kloster says there will be environmental impact studies once the hydrogen project is confirmed, and those will include consideration of the buffer zones – perimeter areas – that will be affected when the port is built near Punta Colorada. More recently, FFI acquired at least 15 fields in Chubut for the installation of wind farms and signed an agreement to settle in Puerto Madryn, in the neighbouring province. For the local press, this possible shift in the location of the project towards southern Patagonia is due to the delays in advancing with a new hydrogen law and the environmental impact studies for Río Negro.

Exports and green neocolonialism

A Fraunhofer report, commissioned by the government of Río Negro, assesses the possibilities of green hydrogen production in the province and concludes it can be cost competitive with blue hydrogen by 2030 and with offshore green hydrogen production in the North Sea. Due to its unique natural conditions and location, Argentine Patagonia is probably the region in the world where the largest scale of green hydrogen production can be achieved, the report suggests.

However, activists and green groups are concerned about a new kind of “green colonialism”. The Green Smoke report, authored by Argentine NGO OPSur, suggests that reappropriating land for wind and solar farms, as well as electrolysis plants, added to the intensive use of freshwater and construction of associated infrastructure, could lead to a deepening of social conflicts, with potentially repressive responses that aggravate the deterioration of institutions and democracy.

Kloster calculates that $15bn in green hydrogen exports would represent production of about 7.5 million tonnes per year, which in turn represents demand for 20,000km2 of land for wind power. According to him, Argentina could easily fulfil this potential, as continental Patagonia represents some 800,000km2. That is, 2.5% of it would be used for wind.

“Exports of green hydrogen to European nations like Germany could help them achieve their climate objectives set under the Paris Agreement,” Kloster concludes.

Mural at Comodoro Rivadavia showing national oil company YPF transitioning from fossil fuels to renewables. (Photo by Julian Reingold)

All of Argentina’s green hydrogen plans are for exports. So what about the decarbonisation of local industry? In 2012, YPF joined efforts with Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council to create Y-TEC, a company subsidiary dedicated to developing new technologies. This spawned the H2ar consortium, which represents more than 30 companies interested in exploiting Argentina’s potential to generate low-carbon energy.

Santiago Sacerdote, CEO of Y-TEC, recently said: “The next five years of exports are about oil, then there will be another five years of gas exports, and only then will [green] hydrogen sales come, after 2030… the incentives have to be sufficient so that this curve can materialise.”

Despite Argentina’s potential for renewables, a good part of its national political leadership still believes the country does not have to be one of the greenest in the world. Meanwhile, YPF’s motto for its 100-year anniversary this year is “Powering what is ours”. For Argentina, green hydrogen is likely to be part of this.

Editor’s note: This story was possible thanks to Internews’s Earth Journalism Network grant on Post-Pandemic Green Recovery.