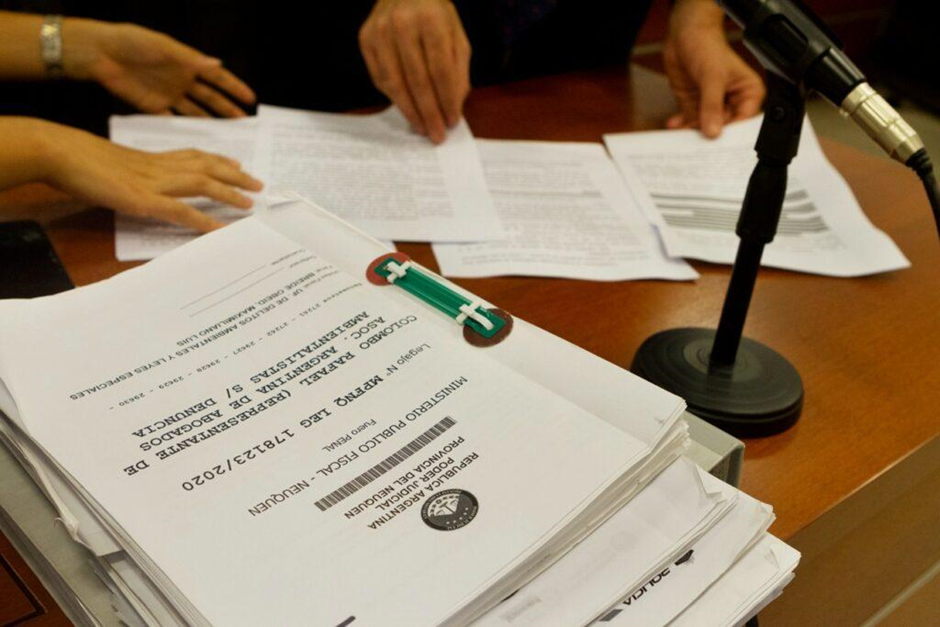

In an unprecedented event, Neuquén’s chief prosecutor has accused Comarsa’s owner and two managers.The company is one of the four waste treatment companies operating in Vaca Muerta. They were charged with the crimes of pollution hazardous to public health and fraudulent management. In their presentation, the prosecutors warned about the risks posed by oil waste stockpiling and abandonment, and estimated the company’s liability at more than 7 million US dollars. The prosecution also reported that the waste site located in Neuquén has been virtually abandoned since 2023. As the prosecutor Máximo Brede Obeid anticipated, “Right now the accused are three, but we are sure there are many more to come.”

By Fernando Cabrera

The prosecution has accused Juan Manuel Luis, Comarsa’s director and main stockholder; Héctor Basilotta, the company’s alternate director between 2014 and 2021; and its CEO between 2013 and 2016, who has requested to remain anonymous. They were charged with running a facility that “systematically received hazardous waste without having the capacity to treat it, creating fake earnings for unperformed treatments, contaminating the environment and compromising the people’s health.” These crimes, which can be traced back to 2014, are ongoing even now at the waste disposal facility in the Western Industrial Park, Neuquén City.

In their presentation, the prosecutors alleged that the mounds of sludge accumulated by Comarsa contain total petroleum hydrocarbons, which include highly toxic volatile compounds such as BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene), HAPs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as naphthalene, fluorene, and phenanthrene), and heavy metals like lead, barium, and mercury, among others.

The amount of waste received by the company exceeded their treatment capacity, which led to a yearly increase in the volumes of stored disposals. Moreover, the company issued waste treatment certificates to the state-owned firm Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), and charged its clients for unperformed treatments. This allowed the company to conceal the real situation in order to continue to receive hazardous waste, keep the contracts, justify its earnings and hinder inspections.

In 2018, the company submitted a plan for waste volume reduction to the Undersecretariat of Environment, in which it acknowledged they had 307,000 m³ of waste. In their plan, the company claimed the waste would be treated through bioremediation or biocells, and at least 200,000 m³ of polluted soil would be buried in secured landfills in Añelo. Like the previous plans, this one was under-executed and unfulfilled. “In March 2023 the company fully abandoned its bioremediation plans, and the waste was sent for final disposal. The prosecution confirmed that the company is no longer using bioremediation. They are doing nothing,” claimed Breide Obeid.

“There are still more than 200,000 m³ of stockpiled hazardous waste, and the only thing that separates the waste from the population that live just about 500 meters from the plant is a concrete wall that is practically in ruins,” stated the prosecutor. Regarding health impacts, he added, “the number of affected neighbors is beyond calculation.” There are densely populated neighborhoods—such as 7 de Mayo, El Nico, Loteo Social and Cuenca XV—just 500 meters from the plant.

Meanwhile, Comarsa’s plant in Añelo has also been closed down, and it is no longer receiving nor treating waste. The prosecutor anticipates that “The prosecution will probably extend the investigation to Añelo because the company has abandoned untreated waste there, and we still do not know what the waste volumes are in Añelo.”

From the contracts signed with YPF, it can be inferred that Comarsa was paid 700 million pesos, although the treatments—which become more difficult with the passing of time—were never performed. The prosecutor didn’t specify the updated sum of US dollars or pesos this payment could now amount to. However, he declared that between 2014 and 2016, when the environmental liability that still persists was generated, Juan Manuel Luis received around 2,375,000 US dollars as fee payments and earnings.

According to prosecution estimates, waste transportation implies around 10,000 truck journeys. The process of treatment, transportation and final disposal could reach a 7,350,000 US dollars liability. “Comarsa cannot respond. The lands are not theirs, and they took the money. Who will end up responding for this? The province and the citizens of Neuquén,” warned Breide Obeid.

The case was opened after a criminal complaint was filed by an organization of environmental lawyers (Asociación de Abogades Ambientalistas) who acted as plaintiffs, a role also taken up by the local organization Asamblea por los Derechos Humanos de Neuquén (APDH). Both took part at the hearing and highlighted the importance of this process in a province where the oil economy is handled with virtually no governmental control. Now, the prosecution will have a year to investigate the defendants and bring them to trial. The plaintiff also anticipated that an epidemiologic survey is being designed and will be carried out in the area.

Precautionary Measures and the Risks of Setting up New Neighborhoods

The prosecution has requested precautionary measures, including a restraining order on assets for Luis, Basilotta, and Comarsa, though the company has almost none since both plants are placed on public lands. These measures were approved by the judge but were appealed by the defense after the hearing. On the other hand, the judge did not agree to request accounting books from Juan Manuel Luis, since it could imply self-incrimination.

The Municipality is expanding street lighting, ditches and sidewalk curbs to set up new neighborhoods near Comarsa. For that reason, the prosecutors resorted to the precautionary principle in order to prevent the division of lands into lots less than 1,000 meters from Comarsa until the facility is cleaned up. The precautionary measure was denied by the judge, on the grounds of being outside the scope of the hearing. “I suppose there will be an environmental impact assessment,” the judge commented. Nonetheless, the risk this housing project involves was put on record. The report has already been delivered by the Municipality to different social actors in the city.

One Step Forward after Decades of Struggle

The filing of charges is an unprecedented event. In doing so, the prosecutors have institutionally heard the complaints that the neighbors living in the vicinity of the plant have been pushing since 2014—Comarsa is polluting, and impacting their health.

In October, 2014, the organization against oil dumps Asamblea Fuera Basureros Petroleros, along with another multi-sector coalition against fracking, Multisectorial contra la Hidrofractura de Neuquén, filed a criminal complaint against Comarsa for its impacts on nearby neighborhoods, both in the press and in the provincial legislature.

In response to the complaints, a decree was passed in November 2015—official Decree No. 2263 regulates the activity and urges that plants be located more than 8 kilometers away from the population. More than 8 years after that resolution, Comarsa’s facilities in the Industrial Park still house more than 200,000 m³ of toxic oil waste, with the aggravating circumstances that they are practically abandoned, and the Municipality is setting up new neighborhoods in the vicinity.

The indictment is, without a doubt, a major step towards justice that proves the plundering and polluting nature of oil companies. There is still a long way to go in this investigation:

- The situation of Comarsa’s plant in Añelo—which operates in a similar way as their site in Neuquén’s Industrial Park—should be analyzed, as was highlighted by the prosecutor in his claims.

- Another subject that still needs to be addressed is the evident connivance of the state officials who are allowing the plants to continue to work to this day.

- On the other hand, the court will have to assign responsibilities to the big oil companies that signed contracts with Comarsa, such as YPF. Although Comarsa has undoubtedly performed inefficient waste treatments, according to Argentina’s Bill on Hazardous Waste, the companies producing the waste must ensure its proper disposal and clean up.

- Indarsa, Treater, and Servicios Ambientales Neuquén (SAN), the other three companies that use oil dumps and operate in the province, should also be placed under strict investigation.

This case, put forward by the people affected and different social and political organizations, opened with a thorough presentation by the group of environmental lawyers, and was luckily met by a prosecution that was open to the plaintiff’s claims. It has revealed the true nature of Vaca Muerta. As one of the plaintiff’s attorneys said, “While some get rich, the waste remains here.”

*Home page photo by: Martín Barzilai / Comarsa’s plant with Neuquén City in the background