The Argentine Sea is vast, and abundant, and there are not only fish in it: the significant potential oil and gas reserves piqued the interest of Argentina’s government and the big oil companies.

Photo: Clyde Thomas @Unsplash

By Victor Quilaqueo / OPSur

The companies advancing on the Argentine Sea’s ultra-deep reservoirs have diverse origins. Equinor, the green re-invention of Norway’s state oil company, Statoil, and other firms from the same country, are at the forefront. Not only accessing sea blocks for exploration and exploitation, but also canvassing the continental platform, the previous step for new extensions of extreme energy’s frontier in the sea. These companies use the experience acquired in the North Sea to position themselves in southern waters.

Offshore exploitation in Argentina is still relatively new. That’s why, when in 2018 and 2019, eighteen offshore blocks were tendered to a handful of large oil companies (see map below), we decided to look at it in more detail. Our organization found then that significant steps had been taken to incorporate huge portions of the sea into the market. In 2016, two situations occurred that illustrate the speed and maneuverability of the campaign to expand the extractive frontier in search of ultra-deepwater fields. In March, the UN ratified the outer limits of Argentina’s continental platform, which meant that more than 1.7 million km2 were recognized under the country’s jurisdiction by the international community.This represented a significant geopolitical event of relevance for Equinor, given that the next step for validating its soverignty was deepening its presence in Argentina.

Another event of geopolitical importance took place in September of the same year. The Argentine Chancellery arrived at a series of agreements with representatives of the government of Great Britain that were embodied in the Foradori-Duncan Agreement. Among the various issues, one goal was key: “To adopt appropriate measures to remove all obstacles that limit the economic growth and sustainable development of the Malvinas Islands, including trade, fishing, navigation and hydrocarbons.” It was clear that intentions over the South Atlantic and Argentine’s continental shelf were taking a different turn.

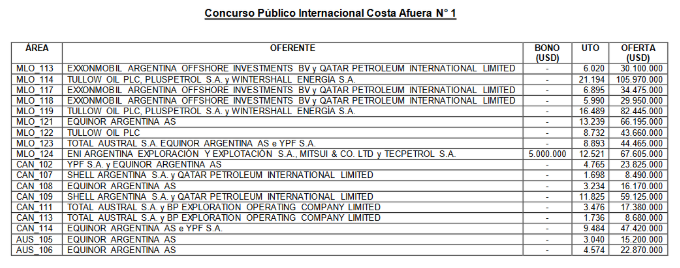

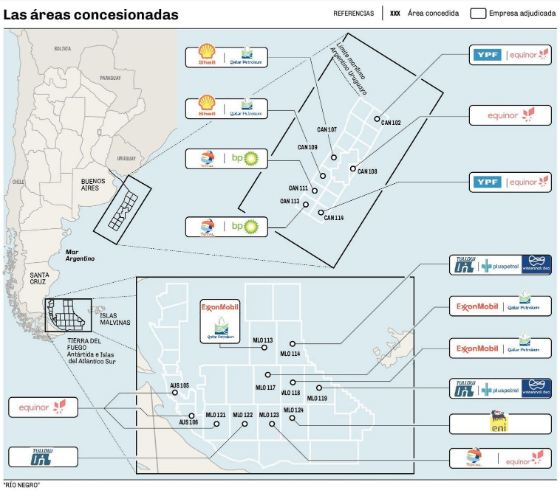

In 2017, the Argentine government authorized the Norwegian company Spectrum ASA to map with 2D seismic exploration, in a series of campaigns, both the northern zone of the continental shelf and the Austral and Malvinas basins. In October of the following year it took another step in the same direction, launching the International Offshore Public Contest N°1, the energy policy aligned for the arrival of global actors. The results were published in May 2019. The Argentine Sea bidding round culminated with the concession of 18 sea blocks, which were distributed among Equinor, YPF, Shell, Tullow Oil, Total, Wintershall, BP, Qatar Petroleum, Exxon Mobil, Pluspetrol, Tecpetrol and Eni. The Norwegian company obtained the largest number of concessions – seven blocks – four exclusively, and three with shared ownership – two with YPF, and one with Total and YPF, respectively. In the same year, another Norwegian company, TGS AP Investments, was authorized to carry out surface and 3D seismic exploration in the northern section and in the Austral basin.

A few days after the results were published, the Malvinas issue went straight to the courts and the media, showing that the agreement signed between the representatives of the Argentine and British governments only paved the way for corporate exploitation . The mayor of Río Grande, in Tierra del Fuego, Gustavo Melella, filed a precautionary measure to declare null and unconstitutional the award of the MLO-114, MLO-119 and MLO-122 blocks to the British company Tullow Oil, and the MLO-121 and MLO-123 blocks to Equinor. Although the action was rejected by the Justice, it highlighted the memory of the war conflict and the claim of Argentine sovereignty over the South Atlantic islands and the continental platform. The mayor underlined that the companies would use these operations to gather strategic information about the continental platform. The challenge to Tullow Oil rested on its British Origins, while that to Equinor focused on Anne Drinkwater, a member of the company’s board, who advises the Kelper government on oil issues.

Souce: Río Negro

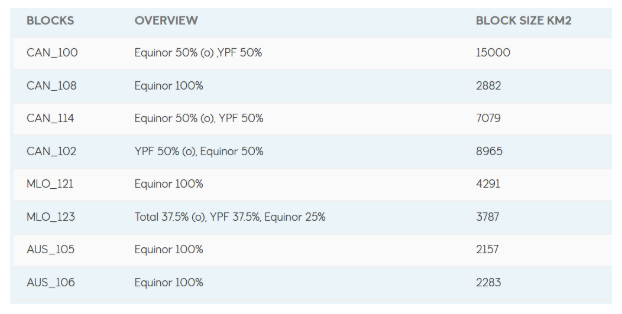

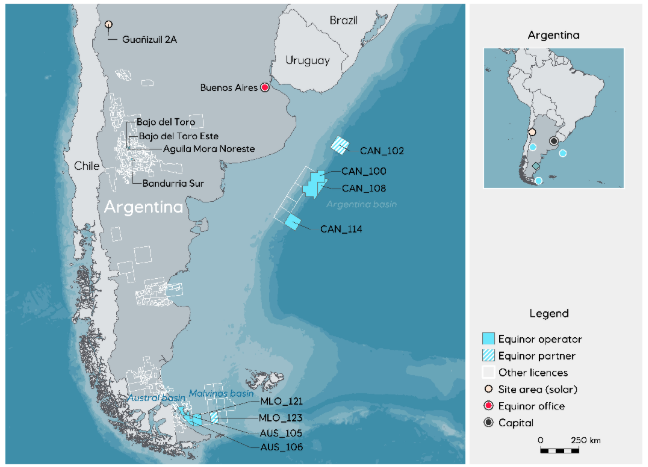

Adding to Equinor’s seven blocks from the International Offshore Public Contest N°1 is the CAN-100 block, which was accessed through an alliance with YPF, with a 50% stake. In this way, the Norwegian company’s presence in the Northern Argentine Basin includes four blocks, plus two in the Southern Basin and another two in Western Malvinas.

Source: Equinor,

Source: Equinor

Southern Frontier

According to this report on European companies set to conquer Vaca Muerta, Equinor’s arrival to Argentina aligns with its greater expansion framework for Latin America, which Equinor initiated at the beginning of the millennium, orienting to offshore blocks and exploratory campaigns. The extraction of gas and oil to which the company is dedicated represents a deepening of policies promoting extreme energy in conjunction with the expansion of the extractive frontier towards distant or new territories alongside technological advances.

In addition to its presence in the Argentine Continental Shelf, Equinor is a player in offshore border expansion in Nicaragua, Mexico and Brazil. In the case of Brazil, Equinor confirms its drive for oil and preference for extreme energies, beyond its speeches about adapting to the climate crisis. . In Brazil, Equinor maintains a presence in the Campos, Santos and Espiritu Santo basins, which positions the company as an important actor in the deep water pre-salt mega-reservoirs. According to the company, this is one of the most important projects in its international portfolio, in fact the Peregrino field, located 85 km off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, is Equinor’s largest project outside Norway, from where it extracts between 70 and 80 thousand barrels of crude oil daily.

The effects of this expansion towards the sea have been strongly felt in Brazilian beaches, bays, ports and cities. The violence of the energy sector, represented by Equinor and Petrobras – among others – affects thousands of fishing families on a daily basis, who are left without access to their resources or whose activities have been interrupted by deep-sea traffic, seismic surveys and pollution, among other adverse effects. According to the report, New Frontiers of Energy Extractivism in Latin America, by Oilwatch Latin America, in all stages of development and exploitation of pre-salt “there is a permanent and systematic violation of economic, social and environmental human rights of traditional peoples of fishermen, quilombolas, indigenous peoples, peasants and other social groups of the countryside and urban industrial districts living in the region of the developments.”

Underground and mainland

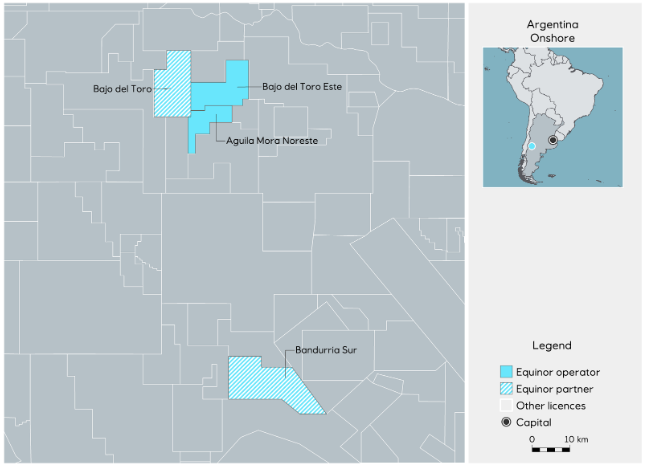

Equinor not only participates in extreme energy projects in the sea, but also inland. In Argentina, Equinor is present in the megaproject Vaca Muerta, in the areas of Aguila Mora Noreste, Bajo del Toro Este, Bajo del Toro and Bandurria Sur. Although the first three are in the exploration phase, it should be noted that they partially overlap with the zone of affectation of the Natural Protected Area Auca Mahuida. In this conservation area strongly impacted by hydrocarbon extraction, Shell and Total oil companies have promoted fracking projects.

In the case of Bandurria Sur, the area became notorious for a major spill in 2018, when a well failed, which occurred before Equinor became associated with Shell and YPF, , the main operator in the area. It is worth noting that in the first days of June 2020, 16 seismic movements were reported in the region, significant activity in the influence area of the same block in question. And in Añelo, the hottest area of exploitation of the Vaca Muerta shale formation, more than 150 earthquakes were registered since 2015, and 135 occurred in the first ten months of 2019.

Beyond each particular project, the application of fracking is questioned, among other aspects, by the high demand for fresh water, the change in the use of soils suitable for food production, the advance on indigenous community territories, the economic sustainability of the activity and the generation of large volumes of toxic waste with the consequential problem of its treatment and final disposal. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that in 2018 the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights made it clear that, if Vaca Muerta progresses, “it would consume a significant percentage of the world’s carbon budget to achieve the objective of a warming (no greater than 1.5 degrees Celsius), as stipulated in the Paris Agreement,” and therefore considered Vaca Muerta a carbon bomb.

It is true that Equinor in Argentina also bets on the development of renewable sources. In the province of San Juan, Equinor acquired the Guañizuil 2A solar park through a partnership with Scatec Solar, a Norweigen company specializing in solar energy. In addition, Equinor has made progress on its commitment to partner with YPF Luz to develop the Cañadón de Leon wind farm in Santa Cruz, but at the end of May it was revealed that the company had given up on that project as part of a restructuring of its investment plan. In general terms, Equinor in Argentina behaves less like an energy company and more like an oil company by betting on its expansion into the extractive frontier towards extreme energies. The fall in the price of crude oil and the reduction in the consumption of hydrocarbons due to the COVID pandemic put the hydrocarbon sector in crisis. Only time will tell how Equinor will respond to this situation, although it’s already given its signal in Argentina. Perhaps there is more time, still, to change course.

Source: Equinor.