Aspiring to be the ‘next Dubai,’ Anelo sees promises, feels pain of volatile shale oil business

ANELO, Argentina — When petroleum engineers in late 2011 confirmed a massive shale oil and gas find in a Patagonian rock formation known as Vaca Muerta, this tiny hamlet lost in central Argentina’s Neuquen province, for a moment, fancied itself as the next Dubai.

Anelo, with a population of 2,689 and a reputation for quality of the local grapes, was on the fast track become the hub of one of the world’s most ambitious extraction projects. The influx of workers, engineers and oil executives would turn this speck on the map into a cosmopolitan city of 30,000 in less than a decade, local boosters hoped.

It hasn’t exactly happened that way, but with Anelo sitting atop what is believed to be the world’s second-largest reservoir of unconventional oil and gas resources, the fracking and technology breakthroughs that have revived U.S. energy production and revolutionized the global energy balance of power over the past decade may be coming to Argentina next.

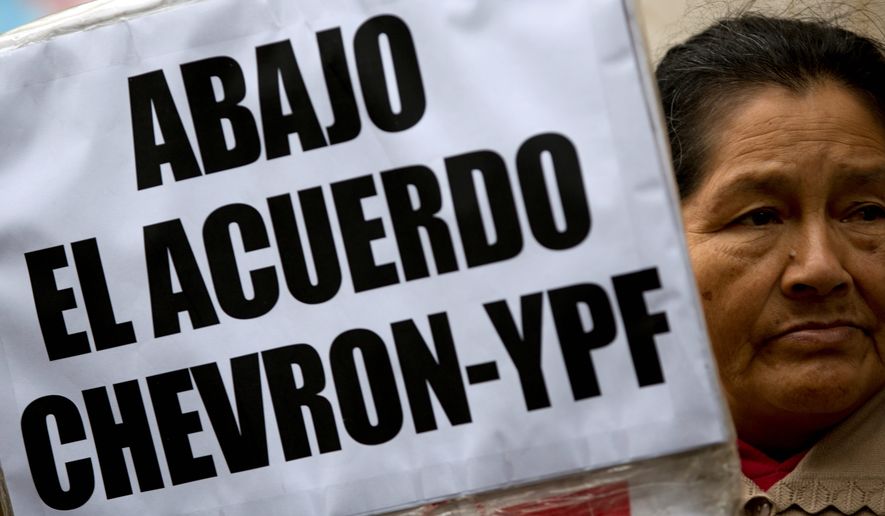

In mid-2013, leftist President Cristina Fernandez cut a $1.6 million deal with California-based Chevron Corp., and rumors about secret talks with Russia’s Gazprom soon were making the rounds.

Then came the great oil bust of 2014, and the price of crude dropped from $115 to $30 a barrel. Instead of paved highways, high-rises and an airport, Anelo got its first taste of the volatile booms and busts of the energy business.

To make matters worse, a 2015 presidential election meant that politicians in far-off Buenos Aires had little appetite for spending money in a sparsely populated voting district.

“We were in a political year, and there were agreements the federal government did not live up to,” Anelo Mayor Dario Diaz said. “That set us back in terms of infrastructure.”

The election result led center-right entrepreneur Mauricio Macri to succeed the populist Ms. Fernandez.

It also gave Anelo a second lease on life as an industrial hub, even though the town had to downsize its expectations of exponential growth.

Mr. Macri, who within months of taking office settled a grinding 14-year battle with international creditors over Argentina’s defaulted debt and began courting foreign investors, has worked to recover much-needed credibility lost under Ms. Fernandez, Mr. Diaz said.

“This new model of a federal government gives [investors] more confidence, and it is taking steps and making cuts so that business is truly profitable,” the mayor said. “If whoever is coming to invest doesn’t make money, he won’t come; that’s just the way it is.”

The Macri government also abolished a complex system of domestic energy tariffs and subsidies that industry analysts say distorted the local markets, scared off foreign investors and rendered Argentina a net importer of energy despite its vast domestic reserves.

The curious from around the world, though, are once again pouring into Vaca Muerta, which the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates holds as much as 16.2 billion barrels of shale oil and 308 trillion cubic feet of shale gas, making it one of the world’s most significant reserves of “unconventional” petroleum products.

“With the [new administration], more and more delegations began to show up. So the Norwegians, the Japanese, the Chinese are coming, and we welcome them all,” said Anelo economic adviser Gonzalo Echegaray.

Today, Mr. Echegaray said, the companies knocking on his door are more likely to be Exxon Mobil Corp., Total SA, Wintershall Holding GmbH or Royal Dutch Shell PLC. Some 30 of them will be needed to fully develop Vaca Muerta, which spreads out over 12,000 square miles of central Argentina. They can now run their operations without being forced into cooperation deals with YPF, the Argentine energy giant that Ms. Fernandez renationalized six years ago.

Matthew Smith, a correspondent with Oilprice.com, wrote last month, “Bottom line: Argentina is on the cusp of emerging from decades of economic instability and … shedding its status as a pariah state among investors to become one of the hottest destinations for foreign energy investors as the business-friendly policies of Macri gain greater traction.”

Rolling out the welcome mat

Neuquen province, with a long history of conventional oil and gas drilling and an economy highly dependent on the sector, is helping roll out the red carpet, especially to American firms with the know-how and experience in shale oil and gas production, Gov. Omar Gutierrez told The Washington Times.

“Vaca Muerta is the country’s engine, [and] the arrival of American companies has been fundamental,” said Mr. Gutierrez, who plans to take part in an Inter-American Dialogue discussion next week in Washington about the country’s energy potential.

Helping fuel the renewed interest is a sense of stability in Argentina’s future, which is paramount in the oil and gas industry. Big players think in terms of decades and may take years to decide on specific investments, Mr. Echegaray said.

“Those are the time frames of a stable economy. In Argentina, we think that from one day to the next, a guy will show up with a briefcase and say, ‘Hey, I want to buy this,’” he said. “These things don’t happen in the world. So they come, look around, ask about unions, community relations, local know-how [and then] come back six months later.”

Still, Mr. Echegaray said, the investors are not always impressed with the pace at which government tends to move here at all levels. The adviser recalled the visit of a diplomat from an Asian nation who arrived from Buenos Aires with an overoptimistic idea of Anelo’s municipal industrial park.

“Of course, when they told him about an industrial park, he must have imagined there would be a university, a gated-off area and comprehensive security,” he said. “No, no, there was nothing — no power, no running water. He left hopeless.”

The strains are familiar to officials in U.S. towns across western Pennsylvania and central North Dakota, where the fracking boom transformed dying towns, sent populations and wages soaring, and presented a serious drain on local services and infrastructure.

In a way, Anelo officials say, the 2014-15 oil slump turned out to be a blessing in disguise, easing the overwhelming demand for housing and services and helping the local administration build up infrastructure for a population still forecast to double within the next two years.

The town — whose main landmarks 10 years ago were “a gas station and a bakery,” as Mr. Echegaray put it — now boasts an educational facility and a sports complex-cum-indoor pool. The town will soon inaugurate a brand-new hospital and police station.

But longtime resident Sandra Leal, who runs the local fruit and vegetable store, said the influx of people means crowded classrooms for her children while her family still waits for basic utilities such as running water.

“It’s good for my business to have a lot of people,” Ms. Leal said. “We were for change. [But] there are so many [oil] companies, and we thought we’d at least get something beautiful. But no, because the beautiful things are private: We now have a casino, there are hotels, everything, but it’s for their personnel.”

The gap between newcomers with high-paying jobs in the oil and gas fields and old-timers facing a sharply higher cost of living has generated tensions, Mr. Echegaray said.

“A municipal employee today makes about 15,000, 17,000 pesos, and a kid who starts in oil and works in a field makes 50,000,” the difference between a monthly salary of about $800 or $2,500, he said. “So maybe you go buy a sandwich, and it costs 200 pesos; and for the oil guy that’s nothing, and you’re killing the other.”

Renting even a small apartment, meanwhile, is prohibitively expensive even for the local doctors and schoolteachers — while City Hall picks up the bill to keep key professionals in town.

“Today, renting a house in Anelo for four persons costs [$1,200 a month],” Mr. Echegaray said. “It’s as though it were Puerto Madero,” Buenos Aires’ posh riverside neighborhood.

Road rage

The chief complaint among virtually everyone in town, though, is the infamous Route 7, an arduous stretch of roadway marked by an endless succession of pink “Road Damage” and “Men at Work” signs that connects Anelo to Neuquen City, the provincial capital 60 miles away.

Critical to Vaca Muerta’s development, work to expand the dilapidated country road into a four-lane highway has been slow, and mile-long construction sites make for unpredictable journeys for both people and goods.

“It can take you an hour or five. You’ll only know when you hit a big truck moving at 10 miles per hour,” Mr. Echegaray deadpanned. “If you have a rig ahead of you, forget about it. Go back to Neuquen City, have some coffee, and try later.”

But far from acknowledging doubts about the effectiveness of his administration, the governor blames the Route 7 fiasco and other delays of infrastructure under provincial jurisdiction on a “crisis of growth,” suggesting Neuquen is paying the price for its own success.

“You know why the roadways collapse? Because everyone has hope for growth. When you drive on Route 7, you see a need,” Mr. Gutierrez said. “What do we prefer? Empty roads?”

Key to solving structural problems will be “good forward-planning” amid tighter cooperation on the local and provincial levels, said Thomas Murphy, a Penn State shale energy specialist who is part of a U.S. government-backed mission advising Argentine officials.

“That would [mean] a comprehensive plan … to coordinate a number of planning efforts relative to workforce development, on housing-type issues, which can be challenging,” Mr. Murphy said. “[And it] certainly would incorporate broader infrastructure — roads and rail, in particular.”

But critical voices such as the OPSur, a Neuquen-based group that opposes fracking at Vaca Muerta, condemn what they see as a “growth for the sake of growth” approach.

The interests of local leaders and the oil industry have become so intertwined, they say, that effective oversight is lacking, and the province is gambling with precious water and agricultural resources.

“In 30 years, what will Neuquen live from? Contaminated, and without the big investments from multinational companies?” spokesman Fernando Cabrera asked. “Neuquen [today] lives for and by oil, with a government bloated thanks to petro-royalties.”

But in Anelo, for the time being, any such negative talk is drowned out by the hum of oil-fueled progress.

“What we have at Vaca Muerta really is something unique in the world, according to the geologists and the studies done,” Mr. Diaz said. “Now we have to be intelligent enough to take advantage and turn these investments into opportunities.”